ON 30th April 2016, my beautiful son Jay Lennon Gascoigne drew his last breath aged just 22. He had had years of complex mental health issues, combined with self medicating in a desperate attempt to escape his demons.

At the age of 22 he gave up on the system and the system seemed to give up on him. For the past two years of his life he slipped into decline and ultimately it cost him his life.

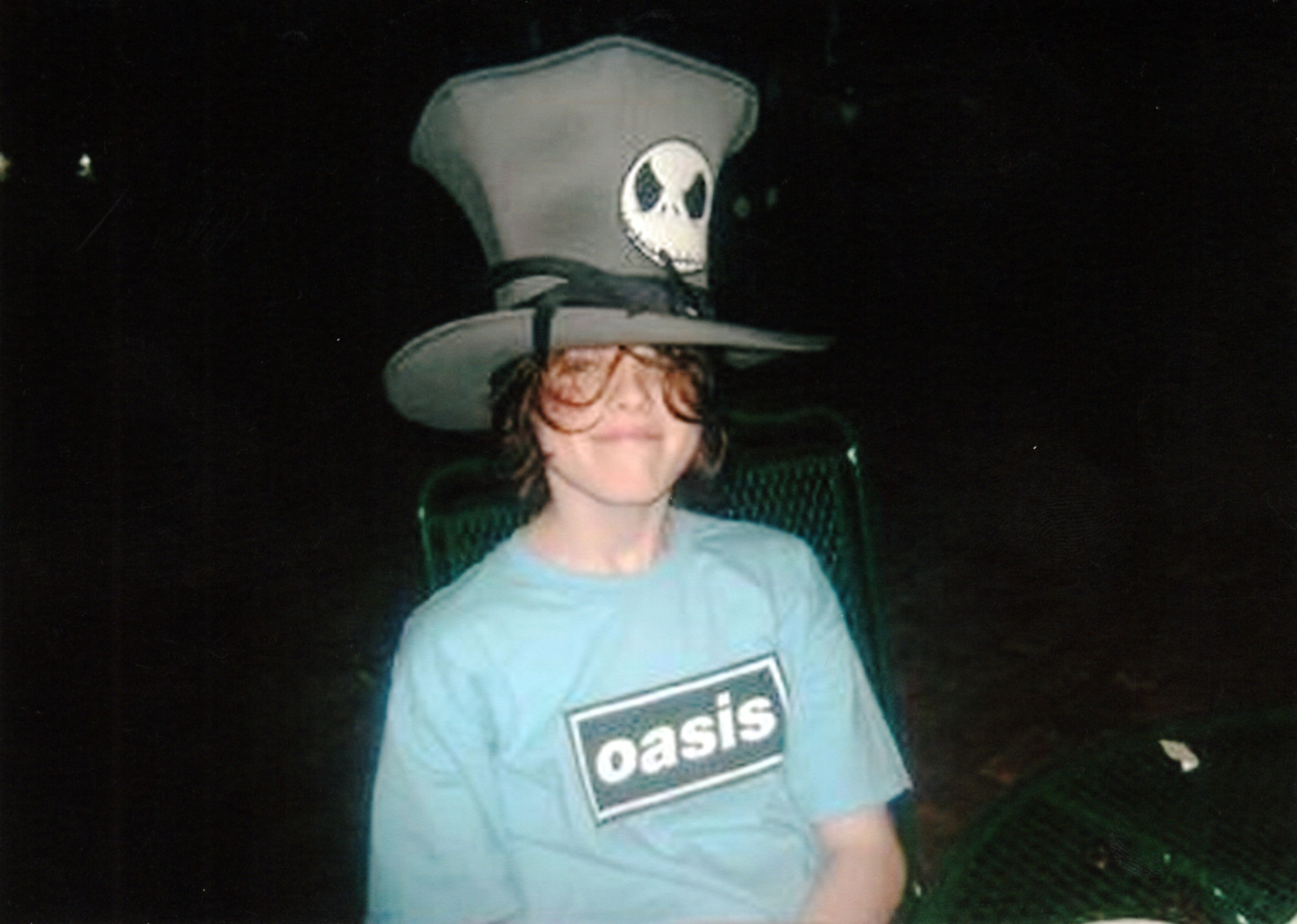

Born prematurely, Jay had a happy childhood, surrounded by my extended family ,who all live on the same estate in Gateshead, Tyneside. Jay’s father John walked out on us when he was six, which impacted enormously on him and his sister Harley, but my family rallied round.

While his uncle Paul was loved by most, unfortunately a few were not fans and as a small 12-year-old, Jay was bullied at school beyond words. Just a week after he started senior school, one even broke his arm.

He developed anorexia and wouldn’t eat and drink. Shortly after he developed OCD, with depression, anxiety and self-harming and was later diagnosed with anorexia. Aged 13, Jay was taken into a residential children’s unit for mental illnesses.

It was a hard journey, but we had a good mental health services support network and we got our Jay back. But once he reached 16, that level of support stopped and there was little continuity.

Jay got through college and he was so ambitious. They always said Paul was the talented one, but Jay had an equally amazing gift for writing poetry, lyrics and songs which he played on his guitar.

Please help us to fund a centre for those in crisis through either mental health or addiction.

But by the age of 17, his OCD and depression really took hold and the help just wasn’t there that he’d had as a child. Jay suffered devastating intrusive thoughts. These thoughts meant he believed he couldn’t blink, or even get a glass or water without being racked with a fear something terrible would happen.

It was like a constant, mental torture that impacted on every part of his life. Over the past two years Jay’s mental health went into decline. But when he started an apprenticeship for environmental charity Groundwork alongside me, I hoped it would be a turning point.

We prayed he’d find a focus away from his OCD, but in November 2015 he was in hospital, then in December and January 2016 he had further hospital admissions, including when he self harmed, causing a massive infection that affected his heart and other organs.

By then, he’d started taking prescription painkillers as they would give him some peace from his mental pain and physical pain, in addition to antidepressants for his depression.

In March 2016 Jay was admitted to hospital for the final time after his mental health declined further and he collapsed.

When the mental health team came down, Jay said he knew he needed help, both with his mental health issues and to also withdraw him from prescription painkillers. He begged, ‘Please section me, I’m not getting the help I need’. They said, ‘You are not appropriate, you need detox for prescription drugs’.

Then we took him to drug and alcohol services. They said there’s a 10-day programme and they told him to come in on Monday. Jay felt so positive for the first time in about two years. But they just gave him paracetamol, something for nausea and something for stomach cramps and sent him away.

They said he didn’t need detox because he was not an addict. This was 10 days before he died.

I spent much of the day with Jay on April 29 when he had to go for a Personal Independence Payment assessment, which had continued alongside his apprenticeship wages. The assessment was intense. He said to the medical assessor, ‘I’m fractured’. All she was there to do was to write a note to the DWP. But he wanted them to know how much pain he was in.

Afterwards he told me he wanted to go and see his girlfriend Jade. So I bought them some food from Greggs and said, ‘I’ll see you later’. Then there was a split second pause where we just looked at each other, before he came over, put his arms round me, kissed me and said, ‘I love you’.

Thank God I heard those words for the last time.

Later, I phoned him at his girlfriend’s, saying, ‘Do you both want to come over?’ He said, ‘Jade’s at work I’ll just wait for her coming home’. I thought he was OK.

When Jade came home she found Jay unconscious and she performed CPR until the paramedics and police arrived. There was nothing they could do to save him. He’d told her hours earlier, ‘I love you. The adventures we’ll go on when I get better’. So he didn’t want to die. As soon as I got the call I jumped out of bed sobbing – somehow I just knew I’d lost my son. My heart fractured on that day and it will never mend.

On the day of his death, a letter arrived from mental health services at the family home, inviting him to an assessment.

I just felt anger, that it was too little too late. In the months after his death I channelled my grief and formed the idea to fund specialist hospital beds for men and women like Jay who beg for help, but don’t get it, because they are not a risk to others or themselves. But they still need help.

I know I can’t bring back my son, and every day I say good morning and good night, knocking on his bedroom door. His guitar still has pride of place in the sitting room where it always stood, but now I tend to his memorial garden at my home. I’ve lost so much. But I hope by raising money for a centre in Jay’s memory, something can be done to help all the other young people who fall through the cracks, who fight and beg for help and become just a number.

Like my Jay, they deserve more than that.